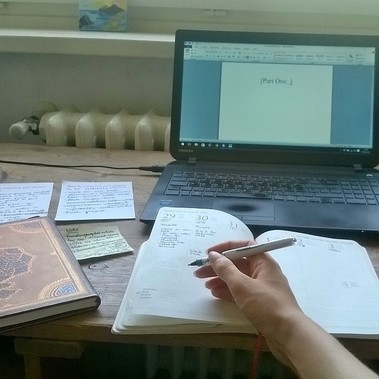

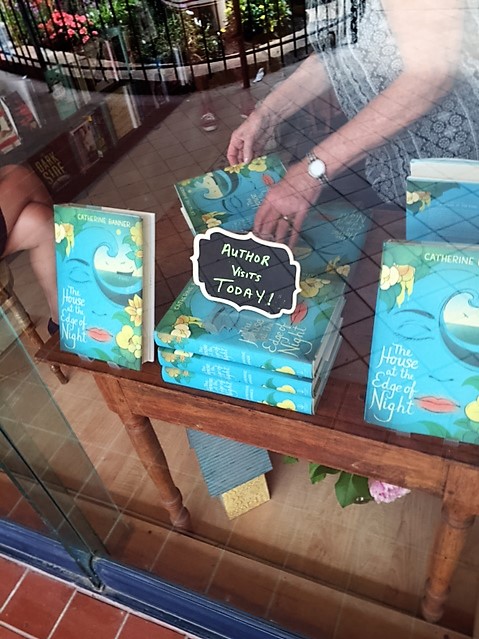

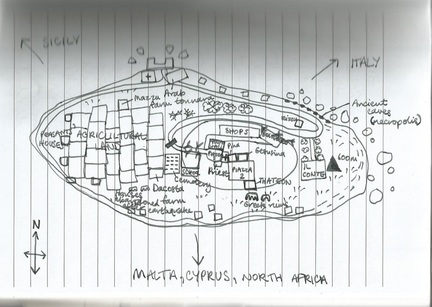

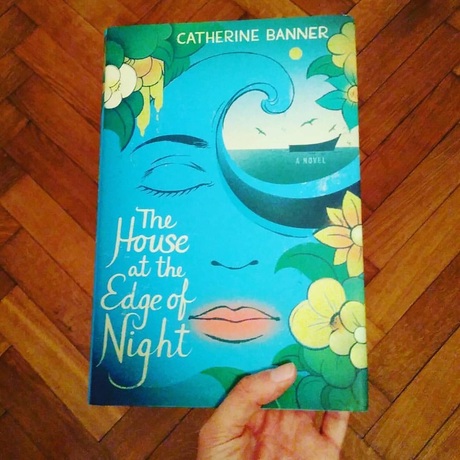

Over the past few weeks I've been silent, partly because I ended 2016 with very mixed feelings and quite exhausted, like many others, but also partly because I've been working on various positive things which will be happening in 2017. Including: my next book, which is due in to Penguin Random House at the beginning of the summer; plans for Italian publication of The House at the Edge of Night; plans for paperback publication (in English) of The House at the Edge of Night; setting up a group with fellow writers to support free speech and equality; and a not-for-profit project called VOICE for which I'm the writing advisor (more about all this very soon). And, of course, I've been spending time with friends and family and away from the internet, which has been restorative. But I did have time for some research in Sicily just before the holiday break, and so here are just a few photos of that beautiful place which was the starting point for The House at the Edge of Night and which will probably find its way, in some form, onto the pages of Book Two as well.

Thank you to all my readers for your steadfast support for my work, and for writers, in 2016, and wishing you a peaceful and happy start to 2017.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed