It can be fascinating to read these notebooks, especially when it lets you track the gestation of a piece of work you have admired. Below are two writers' notebooks which I've read and drawn inspiration from in my own development as a writer:

I began my notebook just as I was finishing The Heart at War. At first, I didn't write in it every day, but only when ideas appeared or when I had some specific research to record. Gradually, though, I found myself writing more and more in it, and now it's become an essential part of my writing routine. I begin by writing the date at the top of the page, and here's what can be found inside:

- Each day's plans. At the start of every morning I record what I'm going to work on, how long it might take, any practical or non-writing tasks like this blog post or a trip to a reference library which I want to find time to work on, and any research I'm planning to continue with or pick up that day.

- Any problems which arise, e.g. a scene that seems poorly worked-out when I come to write it or a character whose motivations need rethinking. I also note down any possible solutions, so that I can leave these and come back to them later.

- Fragments of narrative, dialogue and description to include in the book. Also some drafts of sections of the story.

- Lists of titles. I usually find a working title for a book early on, but this time it took me about ten pages of notes! Chapter titles also take some thinking.

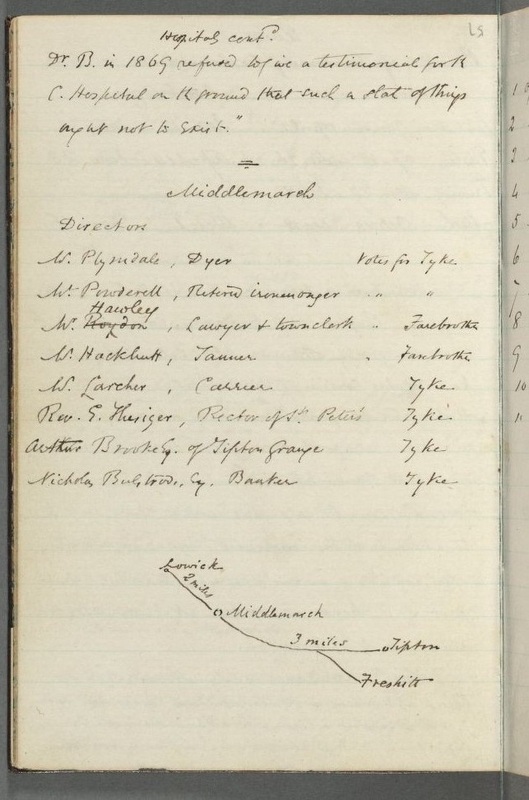

- Timelines of the order of events in a particular scene or character's life.

- Family trees and character lists.

- Rough maps and charts.

- Research notes.

- A running bibliography of all the sources I've used so far.

- A running reading list of all the books I want to read in the future.

- A running word count that lets me see what I've achieved each day and whether I'm on track.

- Field notes on locations I've visited.

- A record of all the important phone calls and meetings I have with my agent, editors and other people who work with me on the books, including what we've discussed and what the next steps are - it can be surprisingly easy to forget when these took place and what you agreed on!

- Notes on interviews, articles and books which I've read and which might help inform my vision as a writer, or which I want to think in more detail about. For instance, during the last month I've made notes on Salman Rushdie's ideas about the writer in the world, gleaned from a fascinating interview I watched last year and returned to recently; a podcast with Louis de Bernieres on history and magical realism; an interview with Kiran Desai about the method of construction of The Inheritance of Loss; and several articles about particular themes in 20th century history.

- Then, at the end of each day, a record of what I've worked on, how much I managed to achieve, and what the next day's plans are.

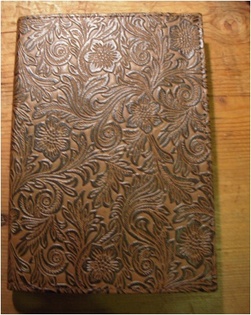

And here's what my writing notebook looks like. There were a few practical requirements: generally, a writer's notebook has to be the right size to fit in a handbag or pocket but thick enough to store a substantial number of notes (as well as strong enough to withstand being carted around for months while said notes are being written!):

How about you? Do you keep a notebook or journal? Let me know your thoughts in the comments below.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed