*Or else start line, depending how you look at it!

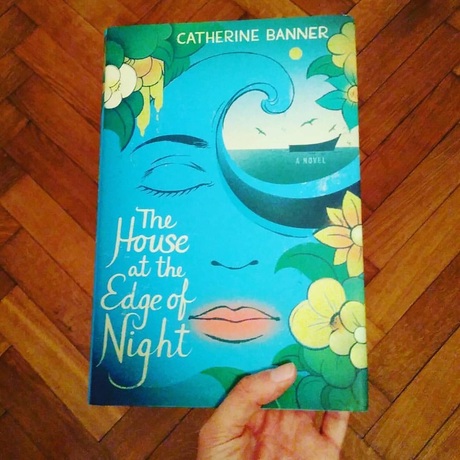

As you will have noticed by now, we have two separate but equal covers for the English-language edition of the book. This is intentional; usually each publisher will try to design something which fits with the culture of their country and which will be meaningful to their readers. So this beautiful design is the book's cover for the US and Canada. As soon as it arrives, I’ll show you the Canadian edition too. (A note here about international publishing: As a writer, my publishing ‘home’ is split pretty much equally between Random House US, Hutchinson UK, and Doubleday Canada, for different reasons. It’s a testament to each of those publishers that this approach actually seems to work, and work better than if I were published only in one country by one publisher).

As soon as I saw this cover, I knew it was the right one for the book: just like with the UK design, it was almost as though the book had existed somewhere out there in the past, and this was already its cover. At least, that’s the best way I can describe it: as feeling kind of inevitable, like déja vu. With both designs, it was almost uncanny to see the images for the first time and feel that the designer had captured something about the book which I couldn’t have expressed myself. For a long time, therefore, I assumed that this meant that the idea for the cover had come to the designers fully formed, in a stroke of inspiration. Instead, as I discovered, this cover, like the UK one, was the result of a very patient process of development over several weeks and months. It’s like writing, I guess – if you’ve done your work correctly, you will have covered your traces and made it look effortless, but worked incredibly hard along the way…

This beautiful design is by Robbin Schiff and the illustration by Edel Rodriguez. You can read more about Edel’s work here. I think this cover is completely unique and beautiful, and I hope you like it too.

And finally, in the spirit of sharing beautiful images, my publishers have launched a Pinterest board this week, where we are collaborating to create a collection of pictures related to The House at the Edge of Night: the places in the book and the research and writing process. It’s a very fun and creative idea, and you can find it here if you want to take a look at what I’m posting each day.

All very best,

Catherine

PS: An unrelated word about this week in news, and why I’ve chosen not to write about it. Like anyone British or partly British, uppermost in my mind at the moment, of course, is the misguided and worrying Brexit vote which occurred last Thursday. As well as this, there are many other things to make us feel sad and angry as European and world citizens right now, not least the very recent attack in Turkey. On this blog, I alternate between update posts where I tell you news of what I’m doing in my life as a writer, and short essays where I talk about reading, writing and how these intersect with the outside world. Occasionally, these intersections demand a response from us as writers. So I did think about writing an essay which would attempt to tackle the topic of Britain’s exit from the EU and the current situation more generally. But the truth is it takes me more than 48 hours’ processing time to engage with something meaningfully in words, and therefore I want to leave that for now. I hope you’ll understand. For British readers, if you want to discuss these issues directly, Twitter (@BannerCatherine) seems to me at the moment a more appropriate way of doing this because it is a space which seems to favour a plurality of voices, and there I am trying to share essays by various writers who have discussed these issues already much more eloquently and meaningfully than I can right now. Fellow Brits and fellow Europeans, please take care of yourselves and each other meanwhile. - CB

RSS Feed

RSS Feed