January

The year got off to a good start with one old favourite writer, Anne Tyler, and one new favourite writer, Elena Ferrante. In January I read Tyler's latest book, A Spool of Blue Thread. I had heard very polarised responses to this book. Both those who loved it and those who were disappointed seemed to be saying the same thing: this is just more classic Anne Tyler. Which led me to wonder whether a writer has some kind of moral duty to vary their books. Isn't the continuity sometimes the point? To me this book, when I read it, seemed to be a variation on old themes not because Tyler couldn't think of anything else to say but because, like all good writers, she is preoccupied with questions which seem to her too complex to answer in one book, and therefore she returns to them over and over. And it isn't just Tyler who does this - most of the writers I love intentionally say the same thing all their lives, refining only the words in which they say it. So yes, stepping into this book requires you as a reader to be willing to inhabit a world with the same air and light, the same texture, the same characters, as Dinner at the Homesick Restaurant or Saint Maybe or many of the other classic Anne Tyler novels of twenty or thirty years ago - and perhaps it has a slightly smaller frame of reference than those novels offer. But in returning to familiar themes Tyler also adds new rooms to the house of her work, and for me, that makes the book worthy of its good reviews and prize nominations. She isn't just reworking old ground; there is also a lovely and understated new story here about family and aging and love.

January was also the month that I continued reading Elena Ferrante, a journey that has been rather longer for me than for most Ferrante fans because I've been trying to read her work in Italian. I completed Storia di chi fugge e di chi resta (Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay) in January. Here in Italy, the third volume of the Neapolitan novels seems to be the one everybody likes the best, because of the way the canvas opens up to deal with some of the most complex aspects of post-war Italian history while keeping its tight focus on the psychology of the female characters and their ongoing struggle to integrate their inner worlds with the demands of the world outside. I think this volume was also my favourite so far, partly for that insight into late twentieth-century Italy and partly because by now, three volumes into the series, my Italian is getting good enough to appreciate the books much more deeply than I could when I started out!

Also read in January: Ada Gobetti's Partisan Diary, translated by Jomarie Alano, which is the memoir of a female partisan and political thinker in Turin in World War Two, Of Love and Shadows by Isabel Allende, Pure by Andrew Miller (one of my very favourite historical fiction writers)... And I officially became the last person with a British passport to have read Paula Hawkins' The Girl on the Train. Better late than never I suppose!

February

In February I picked up the last of Elena Ferrante's books, Storia della bambina perduta (Story of the Lost Child), and surprised myself by barely putting it down again until I'd finished. I've developed a lot of affection for these books, and I could write pages about the ways in which I'm profoundly grateful to Ferrante for this series and what it has to say about being a woman and a writer and a human being, but for now I'll just say that due to the subject matter of this particular book it was gripping in a way that was one part enjoyment and one part horror. Ferrante focuses on the relationship between Elena and her daughters, and the nature of motherhood, and there's a twist related to this theme which jarred with me when I first read it because it is so awful, but which I ultimately came to understand as the direction the whole story had been leading from the moment Lila threw Elena's doll into the cellar about two thousand pages previously. The Atlantic reviewer compared it to Oedipus - unexpected and yet inevitable - and I think that's true. And the very ending is profound with the kind of understatement few other authors can do as well as Ferrante, in any language. I'm planning now to read these books in English to find out what I missed.

In February, I also read In Other Words by Jhumpa Lahiri. In Other Words is a kind of essay or memoir, written in parallel English and Italian, about Lahiri's inexplicable love affair with the Italian language - an odd, obsessive impulse which she struggles to explain even to herself, and which leads her to take years of Italian lessons, to impose on herself an ascetic period of reading and writing only in Italian, and finally to move her whole family to Rome. Writing in Italian forces on Lahiri a style which is not really her own, in the sense that the complexity of thought belonging to her short stories is gone, replaced by a rather spare, halting style. But what interested me most was what was between the lines, the question of what compels someone to begin to systematically shape her whole existence around a language which has no claim on her, which - objectively - she has no 'sensible' reason to learn? 'I believe that what can change our life,' Lahiri writes at one point, 'is always outside of us.' I find any book in which a writer sets themselves an experimental challenge in an attempt to make a breakthrough in their work fascinating. It's like watching a painter make a series of sketches in a new style, and then - perhaps a few years later, if you're lucky - you will look at the next piece of work they produce and see the traces of those sketches in it and understand something about the process of creation. So what I'm interested to see now is whether the protracted Italian experiment enables Lahiri to make a leap in her English-language work. I expect it will.

And in February I also reread Italo Calvino's Italian Folktales, plus several research books which I will mention in a later post because they relate to the new book I've just started writing and I'm superstitious about saying more...

March

The only book I've finished so far in March is Vanessa and her Sister by Priya Parmar. This book embodies what I love about historical fiction and the work of writers like Andrew Miller, and incredibly it's only Priya Parmer's second novel (having said that, Ingenious Pain was Andrew Miller's first, so maybe historical fiction writers are just exceptionally gifted - who knows?). Vanessa and her Sister is that rare kind of historical novel, an act of ventriloquism that succeeds so well that it reads like a found document from the past. Parmar imagines the inner life of Vanessa Bell, Virginia Woolf's sister, through pages from her fictional diary. What I loved about this book was that it not only added to the sometimes rather overworked Bloomsbury vein but also made the whole subject itself more interesting and profound, by rewriting the familiar story from the point of view of a character often thought of as somehow plainer, duller, more ordinary than the sparkling friends and relatives who surrounded her. Parmar reinstates Vanessa as an artist, mother, sister, carer and thinker in her own right, and by the end you are convinced that in many ways she was the most fascinating of them all. And Parmar's Vanessa is also funny. Humour is a massively underrated skill for a writer to possess so effortlessly as Priya Parmar does.

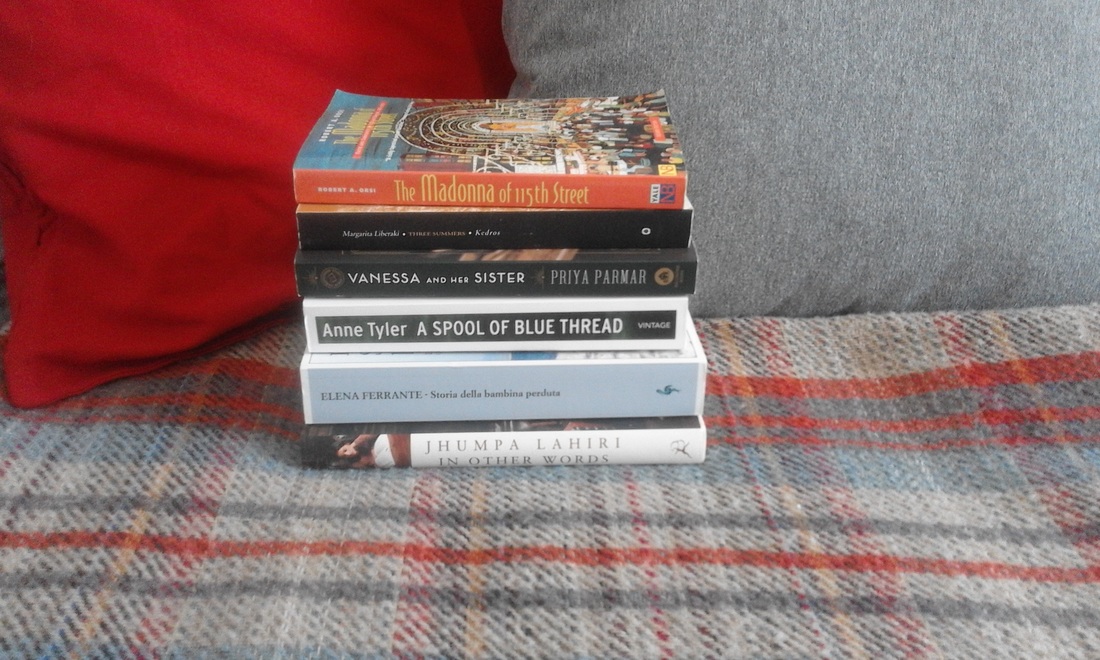

And I'm currently reading: the beautiful Three Summers by Margarita Liberaki, which follows three young sisters in early 20th century Greece, which my good friend Thomai gave me, The Madonna of 115th Street, a study of Catholic popular religion in New York in the early 20th century, Cold Comfort Farm, which I'm reading for a long-distance Skype book club I do with a few of my friends back in England, and Infinite Jest. Of which much more could be said, but I'll wait until I've finished it...

Which books have you enjoyed in 2016 so far? I'd love it if you let me know in the comments. My to-read list is always about five hundred books long, but that doesn't seem to stop me from looking for more books to add to the pile.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed